When collecting vinyl records, you might come across the following terms associated with a special release: live to vinyl, direct-to-disc, or direct-to-acetate.

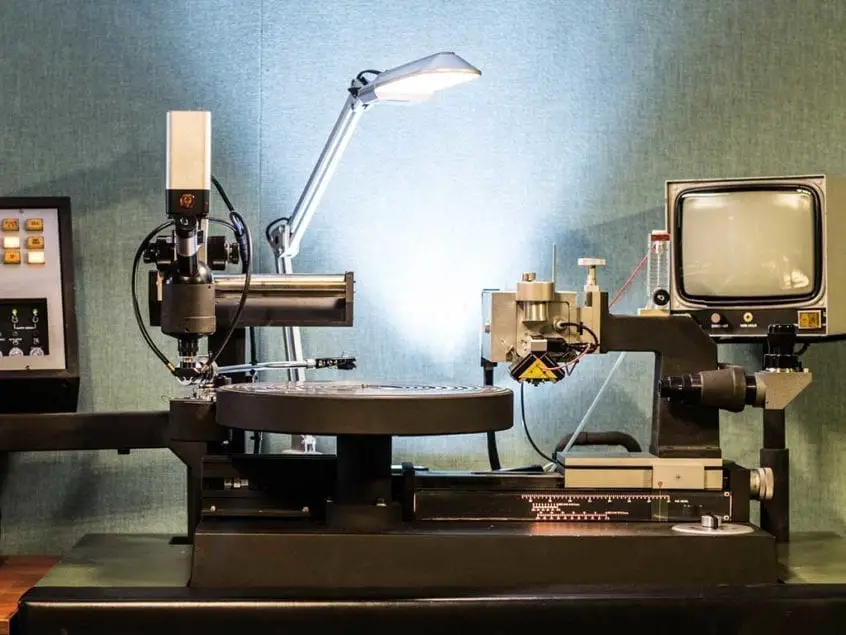

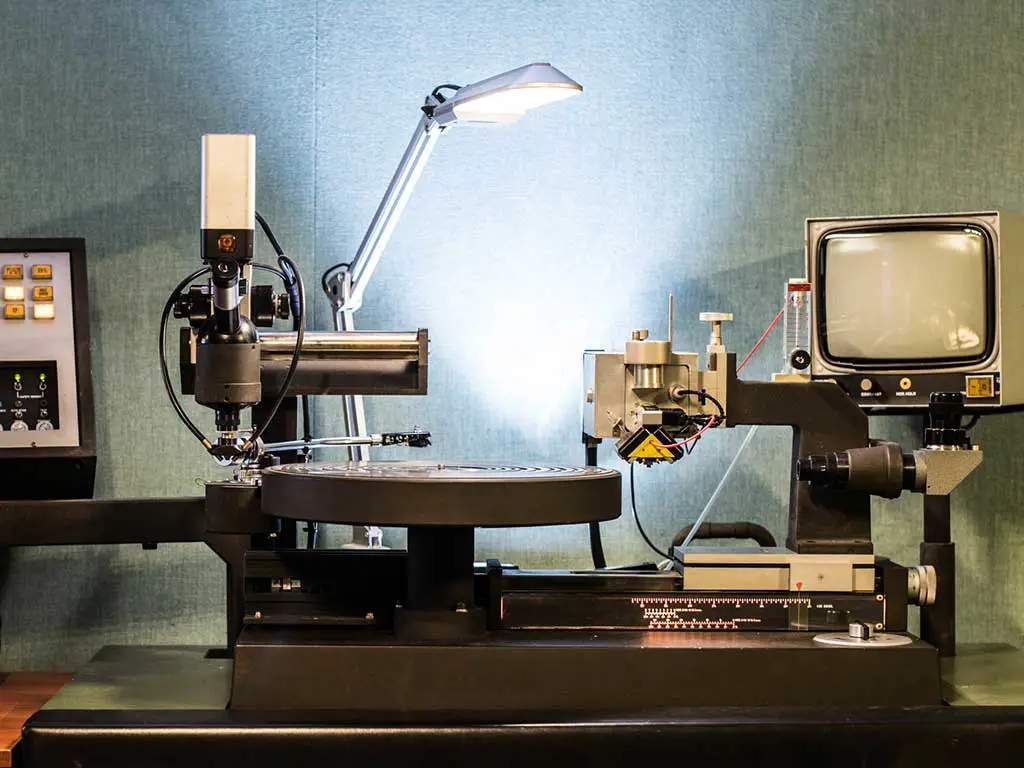

All of these terms refer to the same process, which as they suggest, is the practice of recording directly to a vinyl-disc cutting lathe without first recording to magnet tape or digital storage.

Before the advent of magnetic tape recording in the 1920s, all audio recording was “direct”. It was a notoriously difficult way to record, as the musicians and engineers had to record a complete session live (one record side at a time) without any serious musical or technical mistakes. If a mistake is made, there is no way of editing in post-production. You simply have to start again.

In the 1970s, the process became popular among audiophile circles—despite the inconvenience—as a way of bypassing the inherent noise and fidelity loss associated with tape. The audio quality gains were considered worth the hassle.

When you consider that each transfer of a recording from tape-to-tape will degrade the audio quality, it’s easy to see why this process gained traction in the pre-digital era. Engineers could avoid all the noise floor and tape saturation to achieve a cleaner final record with superior high-frequency transients.

Why Do People Still Record Direct to Disc?

In recent years, the process of recording direct-to-vinyl has made a comeback. Perhaps the most famous example is Jack White’s Third Man Records, who resurrected the process back in 2013. In the UK, London-based Metropolis Studios run regular “Live to Vinyl” sessions, where full-band performances are recorded directly to vinyl in front of a live studio audience.

Back in the 1970s, digital recording was in its infancy, and so direct-to-acetate recordings offered a way to improve the fidelity of analog recordings. Today, tape quality has improved a lot and the vast bulk of records are made using digtial recording software. So if tape is used less and less, why would you want to record direct-to-disc?

The analog vs digital debate aside, perhaps the most compelling argument is around capturing raw performances. As Third Man Records put it, “We believe that this new/old method of recording is as honest as it gets, bringing listeners as close to the experience of the performance as possible…”

There is something to be said for capturing a moment. Part of the magic of old recordings is the fact performers had to get it right first time. And often, the most magical moments on record happen as a direct result of making a mistake.

The element of human error is something we’ve lost touch with in modern music. Modern recording software makes is possible to produce a record that is perfect in every way. We can “grid” a performance with quantization, correct the pitch of every note, and retake a performance indefinitely. The result is a kind of sterilization of music that leaves the listener cold.

The most timeless records strike a balance between polished studio production and human performance. Where that line sits for you will clearly depend on your own aesthetic sensibilities.

Artists like Neil Young are known for deliberately encouraging spontaneity to capture a moment. When receiving a special award at the Grammys ceremony for engineers and producers a few years back, he explained his recording ethos in detail: “A lot of you out here are craftsmen: just beautiful records, and take great care with every note. And I know I’m not one of them. I like to capture the moment. I like to record the moment. I like to get the first time that I sung the song. I like to get the first time the band plays the song. So there’s a lot of compromises you make to get that feeling, but in the long run, that’s where the pictures are when I hear my words and when I see the pictures while I’m listening. So that’s what we try to record.”

Direct-to-disc recordings offer artists and engineers the chance to remove the temptation of perfection in favor of capturing a moment in time. Check out the process in action by watching the video below. As you’ll see, the process requires a great deal of engineering skill and communication to ensure the whole process is pulled off without a hitch.

Just happened to run across this thread. I was lucky enough to produce a Direct To Disc album for Salisbury Labs in 1978 at the old RCA Studios on Sunset in Hollywood. This was with a large band, and what a pain in the neck, as the last number of one of the sides ended with a double C by the trumpet player, and the Lathe kept “blowing chips” at that note, and we’d have to record the whole side again. The album was pressed on virgin white vinyl, but early in the distribution, to Europe, a defect was reported, and the release was halted. A real collector’s item if you find now.

https://www.amazon.com/Direct-Disc-White-Audiophile-Pressing/dp/B001AN7UMW

Tape didn’t start getting used for professional recordings in the US until the late 1940s with technology that existed in Germany during World War II.