Vinyl records have a tactile quality that simply cannot be replicated in the digital realm, and for many – including myself – this tangible aspect makes up a large portion of the overall appeal.

Unlike a CD – which, while a remarkable piece of technology in its own right, can hardly be called charming – a well-made vinyl record is a beauty to behold.

In fact, when you investigate how records are manufactured, it’s a minor miracle the format even works, let alone looks appealing.

There are so many points at which the process could go awry – and that’s before we even consider the playback procedure, which has its own complications and inherent flaws, such as imperfect geometry and progressively decreasing resolution as the record progresses from start to finish.

Yet, despite the complications, the vinyl medium works, and in fact, the manufacturing process has remained relatively unchanged for decades.

The Vinyl Manufacturing Process

Step 1 – Manufacturing the Master Disc

These flat discs are made from an aluminum core, which is first sanded down to a smooth finish. The discs are then placed on a conveyor belt ready to be coated in a nitrocellulose (nitro) lacquer. Rollers catch the excess run-off lacquer, which is re-used.

Once dry, the nitro finish becomes a thick coating similar to nail polish. (The guitar players among us lucky to enough to own a nitro finished guitar will be very familiar with the look and feel of nitro lacquer).

Before the discs can progress to the next stage, they must first undergo inspection for flaws. Any flaw big or small in the finish is catastrophic for the final result; therefore, the failure rate on inspection is extremely high. On passing quality control, a hole is punched into the center to complete the new master disc.

The factory will now carefully pack the new discs in batches using separation strips between each one to protect the delicate lacquer surface.

Step 2 – Cutting the Master Disc

At the studio, our new shiny master discs are cut using a recording machine called a lathe.

First, the master disc is placed onto the lathe and the protective strips are carefully removed. To secure the disc, the engineer places a vacuum line at the center. Next, a microscope and cutter are moved to the disc’s outer edge ready to perform a test cut. The microscope is used to assess the test groove for any issues.

Once happy, the engineer will begin recording, allowing the lathe to cut a continuous groove representing our source material using a sapphire tipped cutter. The recording is monitored via a computer, which can adjust the spacing between grooves if required. A vacuum removes the scrap lacquer created by cutting.

After the recording finishes, the mastering engineer will assess the cut for any issues before scratching a serial number (and often their signature) into the inner edge of the disc.

The video below offers an excellent overview of the lathe cutting process in action:

Step 3 – Creating the Stamper

To create vinyl records from the master record, we must first create the stamper.

The process begins by washing the master disc before spraying it with tin chloride and liquid silver. Any silver that does not stick is washed away. A duller metal is added to the silver side, which stiffens the disc ready for the electroplating process.

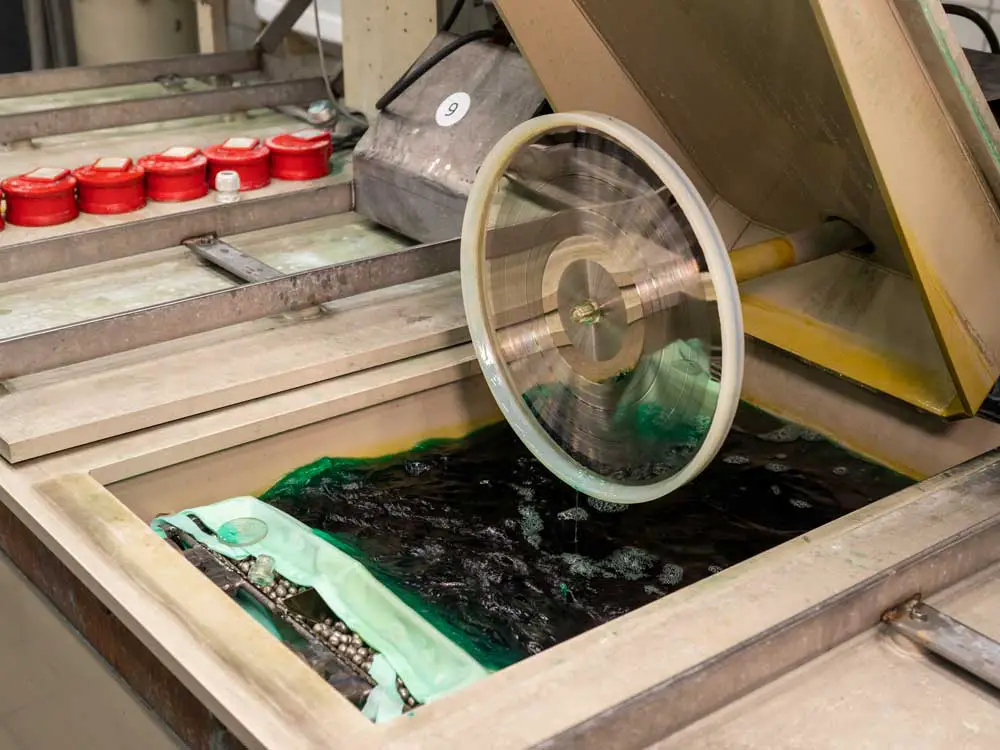

Electroplating simply involves immersing the silver-plated disc into a liquid tank of dissolved nickel. When immersed, the nickel is fused to the silver surface by an electrical charge.

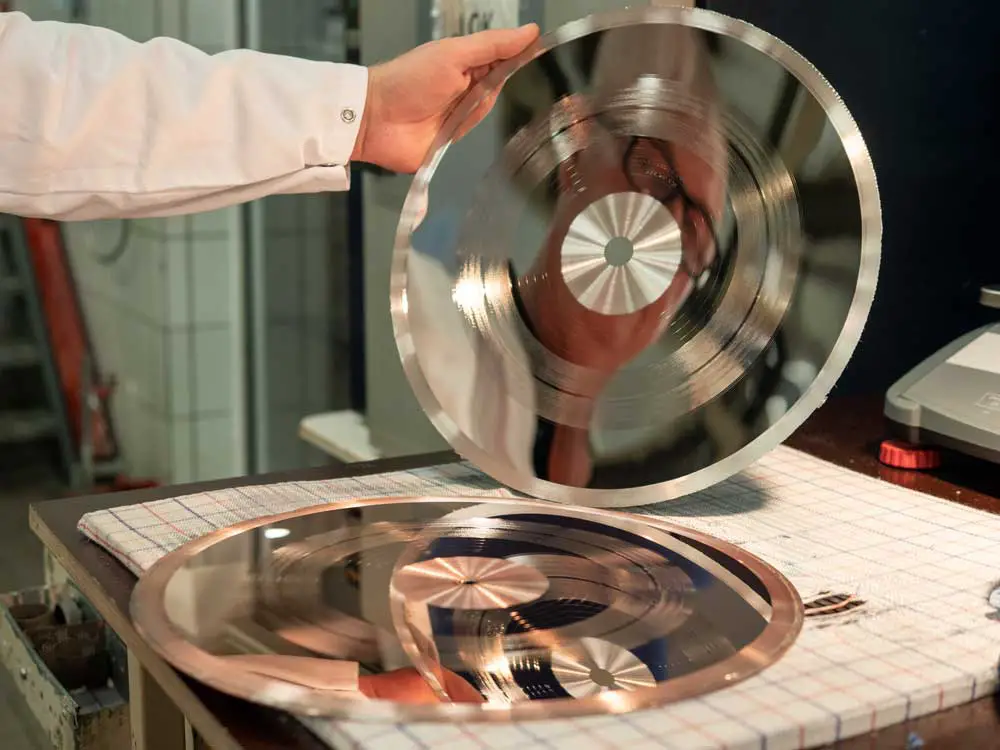

With the nickel set into the grooves, the disc is removed from the electroplating tank and the metal layer is removed from the original lacquer disc. And there you have it; the removed metal layer is our stamper that will be used to press shiny new vinyl records.

To finish the stamper, the manufacturer uses an optical centering punch to make a hole in the exact center before progressing to trimming off any excess metal.

Step 4: Preparing The Labels

The labels must be created first, as they will fuse to the record as part of the pressing process.

Labels are produced in square stacks, which are first punched in the center and trimmed into circles.

Step 5: Pressing The Records

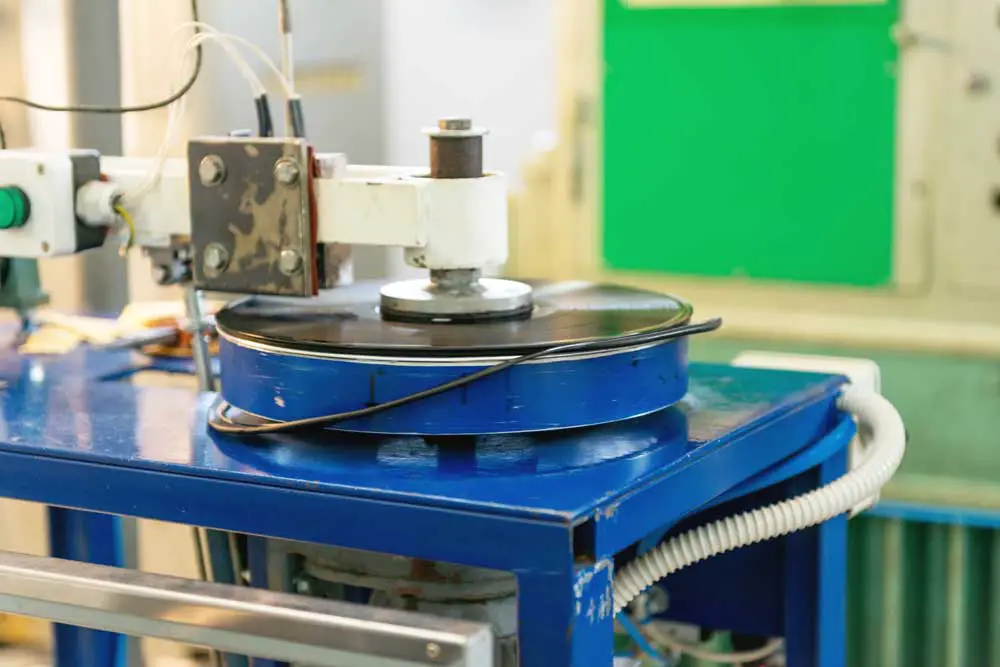

To press vinyl records, the manufacturer first pours Polyvinyl Chloride pellets into a hopper, which feeds the material into an extruder that condenses them into a small puck shape referred to as a biscuit.

The machines hold these vinyl biscuits in place as the labels are placed above and below.

The biscuit and labels are then moved to the press where 100 tons of pressure is applied at very high temperatures to melt and mold the biscuit into a new vinyl record.

Once cool, the excess vinyl is ready for a final trim. Ta da! We now have a beautiful new vinyl record ready for hours of listening enjoyment.

In an age where digital devices absorb increasing amounts of our time, it’s refreshing to know this age-old process is still making an impression on today’s music fans.

In many ways, I find the idea of a micro-stylus tracking tiny grooves to replay music more impressive than any digital playback mechanism.

Some would argue that each vinyl playback is a performance in its own right. A digital file is perfectly repeatable each time it plays, whereas vinyl can change — often dramatically — depending on the maintenance and quality of your record and playback equipment.

Add in the almost hypnotic process of watching your record spin as the stylus makes its journey from start to finish, and I’d say the performance argument is compelling when analyzing why consumers still buy vinyl in the digital age.

thank you for the amusing article.

Absolutely fascinating still don’t fathom this art work itself.

Fascinating indeed. Thanks for the insight.

Thank you for the article,. I enjoyed reading about how records are made. For a future edition could you explain some of the terminology we are faced with when purchasing Vinyl? Which are better than others. e.g Vinyl, ultra disc super vinyl, one-step vinyl, UHQR etc. Also why are some supposedly audiophile records available at £25 and others £180 and up, is it just about rarity or can we expect the more expensive ones to sound better?

What makes the best sounding records is the source material. Analog recordings from multi-track tape has far more information than digital.

Analog is infinite where digital has a number from the compression process.

So keep cleaning and taking care of those old classic recordings.

Spend the extra money and time on those garage sale finds, cleaning them up the best you can

Enjoyed your article. My brothers and I owned and operated a record pressing facility in Marietta, Georgia back in the late 60s – early 70s, until the worldwide so-called “oil shortage” put us out of business. (Vinyl is a petroleum product.) The process as you described is pretty much spot on, except we also printed and fabricated the album covers (jackets) as well. Somewhere in my storage, I probably still have a metal “stamper” or two.

[…] can read in more detail about the vinyl record production process on the internet, for example on How Are Vinyl Records Made? or How Are Vinyl Records Made? (Step-by-Step […]

[…] Once you’re happy with the final test cut, your engineer will cut the final 14-inch master lacquers (one for the A-side and another for the B-side). Traditionally, you would now send these lacquers to the record plant for production. The plant will use the master discs to produce the stampers, which are then used to press your vinyl records. (Read more on vinyl record production, here). […]

Interesting article, thanks!

No worries. Glad you enjoyed it.