Have you just inherited a record collection? Or perhaps, like many, you’re rediscovering vinyl records for the experience and unique sound quality.

There are many different types of vinyl records, and some of the terminologies can get quite confusing.

So if you’re looking to understand what’s in that dusty box in the attic, you’ve come to the right place.

We’ll help you understand the most common types of vinyl record. We’ll also cover some of the more obscure, rare records that can often hold collector value.

By the end, you’ll be an expert in navigating the world of vinyl so you can either enjoy that box for many years to come, or make informed choices about how to sell those records.

The Most Common Types of Vinyl Record

There are four core types of vinyl records that you’re most likely to come across today.

12 Inch LP (Long-playing) Albums

Introduced in 1948, LP albums were a huge improvement on the existing shellac 78 records that were very brittle and limited to less than five minutes of playback per side.

New LP discs were made of PVC (vinyl) and played with a smaller-tipped microgroove stylus at 33 1⁄3 rpm. Each side of a 12-inch record can include up to 26 minutes of music per side.

Initially, the LP was popular with classical music due to the longer playback time. Eventually, pop and rock acts adopted the format in the 1960s as artists took advantage of the longer playing time to create a more complete body of work.

The term “LP” eventually stuck as a way of meaning “album” in the context of vinyl records.

What Speed do 12-inch Records Play at?

Most 12-inch records play at a standard speed of 33 1/3 revolutions per minute (RPM). This has been the standard speed for LPs since their introduction in the late 1940s. That said, many 12-inch records are cut at 45 RPM for audio quality reasons. In theory, cutting at 45 RPM can sound better (see the FAQ section for more on this).

In other (very rare cases) 12-inch vinyl records are cut at 78 RPM, like vintage shellac records, although this does technically make them the same as old 78s, which are made from shellac and have very different groove dimensions requiring a specialist stylus to play accurately.

7 Inch Singles

The 7 Inch (or “45”) is the most common form of vinyl single.

At their peak in the 1950s and 60s, the 7 inch helped fuel the early years of rock and roll culture thanks to their relative affordability compared with expensive 12 inch LPs.

The 7-inch 45 RMP record was first released in 1949 by the RCA Victor company as a more durable and higher-fidelity replacement for 78 rpm shellac discs.

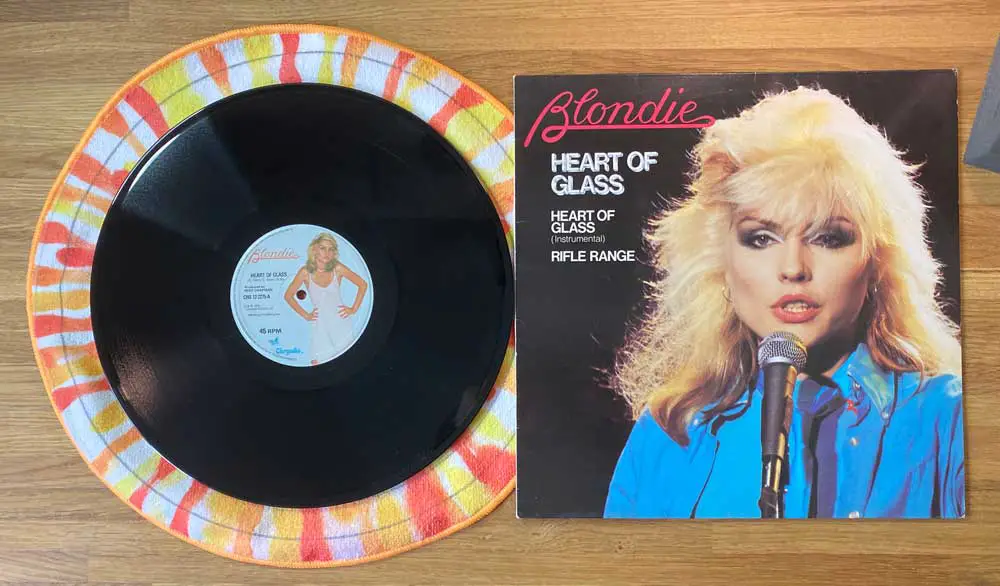

12 Inch Singles

The 12-inch single variation first appeared during the disco era in the 1970s.

Generally cut at 45 RPM, they feature wider groove spacing and shorter playing time compared to LPs, which permits a broader dynamic range or louder recording level (among other benefits.

Twelve-inch records are popular in dance music, where DJs use them to play in clubs. By the 1980s, record labels would often release 12-inch singles containing extended versions or club remixes of pop music.

10 Inch Records

Many of the earlier long-playing microgroove records, were, in fact, 10 inches. And, in many cases albums would consist of multiple 10 inch LPs grouped together to form a multi-disc album release.

It was initially thought that classical music listeners would require the longer playback time of a 12-inch LP, whereas pop music listeners would stand the shorter run time of 10 inch LPs. They were wrong, and the 12-inch LP eventually won the day.

Rare, Unusual and Older Record Types

Beyond your average 12-inch LP and 45 RPM single, you might be lucky enough to come across a few older formats or unusual releases.

78s (Mostly Shellac Records)

Though not strictly ‘vinyl’, it’s vital to understand 78s as part of the mix.

Shellac records (normally called 78s by collectors) were the dominant record format between around 1898 and the 1950s. They spin at 78 RPM, and most were made from a very brittle shellac resin.

78s come in a variety of sizes, the most common being 10 and 12 inches.

Flexi Discs

Flexi Disc records are made of a thin, flexible vinyl sheet. During the peak vinyl years, magazines often used to give away flexi-discs containing exclusive tracks or popular hits.

As you can imagine, the quality wasn’t great as the thin material and subsequent shallow grooves didn’t reproduce great sound. Very nostalgic nonetheless.

Dub Plates

A dubplate is a type of sample disc (referred to as an acetate disc) used in mastering studios for test recordings before proceeding with the final master, and mass-produced vinyl pressing. (Most are 10-inch discs, but 12-inch versions are available).

In reggae dancehall culture, a dubplate refers to an exclusive, ‘one-off’ acetate disc recording that only some DJs have access to. They’re also used by drum and bass and other electronic music producers. These dubplates will often be unreleased recordings, exclusive versions, or remixes of existing recordings.

Traditionally, the material of a dubplate is much softer than pressed vinyl. After about fifty plays, the loss in sound quality becomes noticeable.

Picture Discs and Colored Vinyl

We’ve all seen those picture discs hanging on the wall in record shops.

The roots of picture disc records go back further than you might think.

In fact, they date back as far as 1900, when the Canadian Berliner Gramophone Company had the “His Master’s Voice” dog-and-gramophone trademark lightly etched into the playback surface of some seven-inch shellac records as an anti-piracy measure.

More often, however, when we think of picture discs, we think of collector’s items with full-color graphics over the playback surface.

Sadly, most of these releases are style over function and don’t sound particularly good. Most lack dynamics, and sound thin and noisy.

Colored vinyl is more popular than ever. There is much debate as to how much the color in vinyl makes a difference to sound quality (if at all).

Most engineers agree there simply isn’t enough evidence pointing to one color as better or worse than another.

Even if one color did sound minutely different, there are so many other more important factors, such as the quality of mastering and record production.

The Bottom Line

Music fans of all ages are discovering the joy of vinyl records as a welcome break from the soulless experience of modern streaming platforms.

The development of the vinyl record format over time is a fascinating history. Many different types of vinyl records have come and gone over the years, with plenty of obscure formats, shapes, and sizes that go well beyond the scope of this article.

If you’re part of the growing number of listeners discovering vinyl, welcome on board, we hope this guide helped you understand the format and a bit of its history.

For those looking to sell an inherited collection, you’ll now understand more about what’s passed into your hands. Be sure to check the value of your records using a service such as Discogs before making any rash decisions to sell – you never know what treasures could be in those dusty old boxes.

Commonly Asked Questions:

33 RPM records have always presented a compromise in sound quality, in exchange for longer playback time. 12-Inch LP’s mastered at 45 RPM sound better. There are quite a few technical details as to why this is the case, so for the purpose of this article, I will try to key this simple:

Since 45 records travel faster than 33 RPM, more waveform definition can exist on the record surface; in other words, there are more bumps and grooves created, which means better audio quality.

Does 45 RPM Sound Better – Think of it like drawing a flipbook:

If you drew the same animation on 33 and 45 pages respectively, you’d have to flip your 45-page version quicker to get the same speed animation as the 33-page version, but the changes from page-to-page would contain more detail, making the animation considerably smoother. The higher the RPM, the greater the length of vinyl picked up by the stylus, and ultimately, the more accurate our sound reproduction becomes.

Additionally, longer wavelengths, smaller angles in the grooves, and the less complicated geometry at 45 RPM help to cut very precise grooves with very fine detail.

If that wasn’t enough, 45 RPM cuts experience less inner-groove distortion, as the increased groove velocity helps to minimize the loss of high frequencies and an increase in distortion as the groove moves to the center. The downside to all this, of course, is a reduction in playback time per side.

All of the detail aside, 45 RPM records just sound better (providing they’re mastered with skill and manufactured correctly, of course), and this is why many “audiophile” album releases are 45 RPM LP’s spread over a couple of discs.

All the above is true for 12-inch 45 records as well as the usual 7-inch format.

Most vintage vinyl records weigh between 120 to 150 gram.

In more recent years, there is a trend towards heavier weight vinyl between 160, and most commonly, 180g. These new pressings often carry a label claiming the record as “Audiophile Quality 180g”.

It’s a common misconception that thicker vinyl sounds better. This misunderstanding often comes from the idea that thicker records are somehow cut with ‘deeper grooves’, which is entirely untrue.

As we confirmed in our article cover the topic ‘does 180 gram vinyl sound better’, the technical standards for cutting grooves to vinyl master discs are determined at the mastering stage, not by the record weight.

Therefore, the weight of a vinyl record has little to no impact on sound quality.

Suppose you’ve inherited an old record collection, and you’re thinking of spinning them, or perhaps selling on.

In that case, you can improve the sound quality and value significantly by giving them a quick clean.

There are many record cleaning fluids on the market that make light work of removing those pesky pops and clicks. Just be sure you choose wisely, particularly when cleaning shellac records, as these records cannot be cleaned with fluids containing any alcohol.

Check out our full guide on how to clean vinyl records to learn more.

LP stands for “long-playing”. The term “long-playing” was used to distinguish modern microgroove vinyl records from earlier 78 RPM shellac records, which could only hold a few minutes of music per side.

LP records are typically 12 inches in diameter and play at a speed of 33 1/3 revolutions per minute (RPM). Thanks to the slower playback speed and new microgroove dimensions, they were capable of holding more music per side than 78 RPM records, which allowed for longer and more complex compositions to be recorded and played back on a single disc.

I see on shopping websites such as Hell’s Headbangers the records are either labeled as an LP or MLP, I was wondering if there was a difference.

I’m surprised you didn’t mention 78 rpm vinyl records and the need to use a different stylus, and the need to choose between a mono and stereo stylus and how stereo 78 stylii can play mono but not the reverse.

So what about the 7 inch Extended Play? Where does that fit in the vinyl panoply?

[…] Source […]