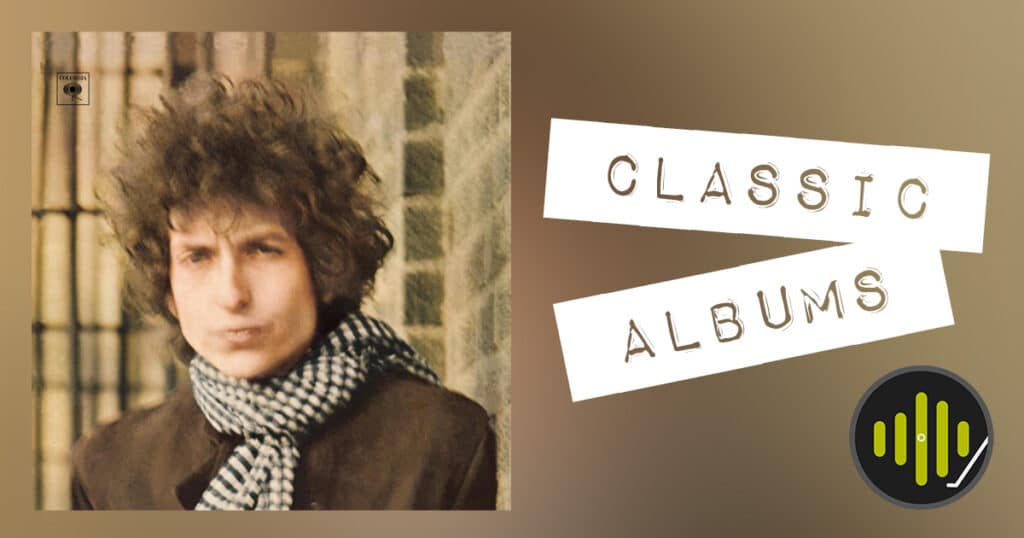

The last installment in Bob Dylan’s so-called “rock trilogy” is an ambitious and accomplished creative crossroads that came to be the perfect pivot point to intersect his hippie minstrel poet past with the electric swagger of his trio of albums in the mid-1960s…

The version of this album featured is the VMP Essentials release cut by Ryan Smith at Sterling Sound from the original mono master tapes.

Hailed as folk music’s Messiah throughout the run of his first four records, he drew the ire of many diehard fans after his stirring live electric band reveal at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. The moment was so significant that the lyric in the kickoff track and single “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35” “everybody must get stoned” is a reference to audience members throwing literal stones at him while performing.

While the Beatles and Beach Boys were all enjoying their own version of success, Dylan would go on to release some of the most defining records of the era, and arguably of all time. With his run of releases starting with Bringing it All Back Home, and Highway 61 Revisited in 1965 he proved, like all great songwriters, that his style can’t be defined.

But it was the seminal 1966 release, seventh in Dylan’s catalog and last in the trilogy, Blonde on Blonde that it became perfectly clear his metamorphosis into this new era of songwriting was complete. The fact that the album would become the first double album ever released by a popular music artist proved that while there were contenders to the songwriting throne, Dylan sat atop it alone.

Recording

When describing his new musical direction, Dylan is famously quoted saying “I know my thing now”. It’s this kind of bravado, this kind of gravitas, and this kind of swagger that gave Dylan a running start when beginning the production for the album. But things didn’t start off very well.

The sessions began in Dylan’s familiar stomping grounds of New York City at Columbia’s Studio A in October 1965. The initial sessions ran until January 1966, but they were marred by unproductivity and Dylan was unhappy with the results. The only track from the Columbia sessions that would make the final cut was “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)”, the last track on side one of album A.

Though Dylan’s manager was very much against the idea, producer Bob Johnston, who also produced the majority of Highway 61, moved the sessions to CBS Studios in Nashville. Johnston was the “artist’s producer”, meaning he was in a seemingly perpetual struggle with the label to not have too much oversight. He believed in letting the artist have free creative control, because it benefited the end product.

This new environment in Nashville provided the artistic breathing room that was needed. The songs weren’t finished yet, so Dylan continued working on them on the piano in his hotel room. Using some of Nashville’s top studio musician talent, the rest of the 13 songs came together over the next two months.

These session musicians would learn the song arrangements as they were born while Dylan continued to create. This unusual approach is one of the reasons there is a free-form looseness to many of the tracks.

Blonde on Blonde saw Dylan’s sound evolve significantly from his stripped down folk roots to more bluesy, experimental songwriting. It became apparent that while Dylan respected the folk roots that he grew from, he had larger ambitions.

Full of powerful and poignant songs in true Dylan fashion, there might not be any of them that cut as much as the final track. Taking up the entire side B of album two, the first of its kind, “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” is an 11-minute long tour-de-force, the perfect coda for a record as ambitious as this.

“We mixed that mono probably for three or four days, then I said, ‘Oh shit, man, we gotta do stereo’…”

Bob Johnston – Producer

Mixing

Mixing took place in Los Angeles in April of 1966, and during the process it was clear that the amount of material couldn’t fit onto just one record. The decision to release it as a double album was a bold move, with Blonde on Blonde being considered the first double album in popular music history.

The version we have on the deck for this feature is a reissue of the original mono mix. Although a stereo version does exist, the mono version was Dylan and his producer’s chief priority at the time.

Mono was still the main playback medium for consumers at the time, meaning early stereo mixes were often an afterthought.

Famously, in an interview conducted by Roger Ford in 2010, producer Bob Johnston went on record claiming the stereo mix was rushed through quickly, stating, “We mixed that mono probably for three or four days, then I said, ‘Oh shit, man, we gotta do stereo.’ So me and a coupla guys put our hands on the board, we mixed that son of a bitch in about four hours!… So my point is, it took a long time to do the mono, and then it was, ‘Oh, yeah, we gotta do stereo’.”

Stereo being novel at the time, it wasn’t uncommon for early stereo mixes to feature hard panning by today’s standard. On the stereo edition of Blonde on Blonde, the drums are often hard-panned to the right speaker, with the guitars hard left. Dylan’s distinct vocals and trademark harmonica are right up the middle, keeping his iconic performances front and center. This approach makes for interesting listening, especially on headphones.

For many, though, Dylan is best experienced as it originally was (mostly) at the time, in good old-fashioned mono.

Release

Released on June 20, 1966 the album would reach the top 10 on both sides of the Atlantic. It reached number nine in the United States and number three in the UK. It immediately resonated with fans, producing five hit singles. It was certified Gold a little over a year after release and would go on to achieve double platinum status.

In true Dylan style, there’s an overwhelming sense of melancholy to the tracks on the record. What makes it worthy of some many repeated listens is the eclecticism in the track listing. Its mix of blues, folk, pop, soul, R&B, and world music is a unique blend that melds well together while feeling it could fall apart at any moment.

Every track flows delicately into the next, creating a cohesion that became a wake up call for songwriters everywhere to step up their craft. When asked to describe the vibe of the record, Dylan described it as “that thin, wild mercury sound – metallic and bright gold”.

Wrapping Up

Blonde on Blonde wasn’t just new territory for Dylan, it was a rebirth. As one of the first double LPs in rock music, he not only achieved new artistic heights that only the best artists to come after him have attempted, he set the standard. The album is so influential that it continues to be a well of inspiration for artists to this day.

Dylan had nothing left to prove.

About the Guest Contributor:

Brandon Stoner is a lifelong musician and audio engineer who owns more guitars than anyone needs. As a lover of all things writing and music technology, he crafts every piece with his dog Max on his lap.

I am a huge Dylan fan and this album is on my want list, even though it is not one of my favorites. My biggest disappointment with Dylan was seeing him in concert, one of the worst live performances I’ve seen. Despite some amazing Dylan covers like Hendrix All Along The Watchtower, he is not an easy artist to cover. Check out his anniversary special at MSG if you want proof, many of the covers were awful. Thanks for featuring this album as it is a classic.