Just a few short years ago, vinyl download cards were considered fairly standard practice. They were part of the package, part of the appeal of buying vinyl – if only as a bonus.

And at the time, it made sense. Digital downloads were still a mainstream format for music consumption, and a downloadable copy made the physical vinyl more appealing and better value for money.

After all, vinyl records sell at a premium price and who wants to buy an album twice if they don’t have to?

But the times, it would appear, they are a-changin’ (as Dylan would put it).

But the times, it would appear, they are a-changin’ (as Dylan would put it).

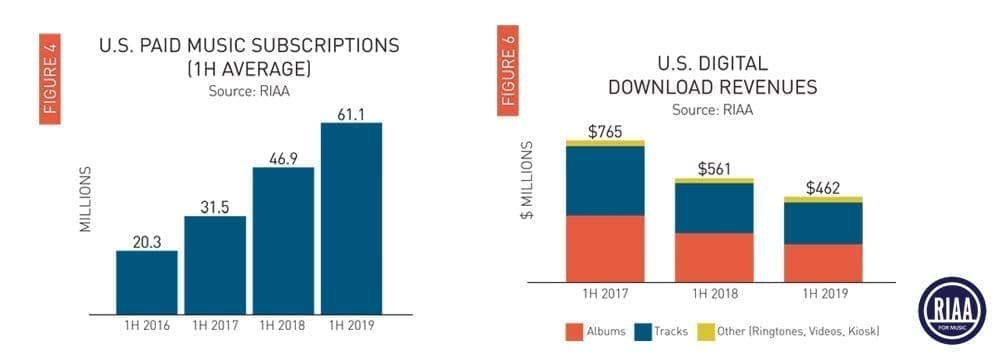

The recent figures released by the RIAA clearly show a strong decline in digital downloads and a continued shift towards streaming services for digital consumption.

In the physical domain, vinyl continues to thrive, while CD sales decline.

These trends are reflected in the actual redemption rate of most digital download cards, which—according to many labels—is very low, and continuing to decline. In most cases, the redemption rate is below 25%.

It’s not hard to see why labels might struggle to justify the time, cost, and materials involved in supplying a download code to satisfy a minority of consumers. After all, streaming services are cheap and highly convenient. But is this a positive or negative trend?

The answer to this question all depends on your perspective, and your individual consumption habits. I, for one, haven’t yet made the switch to streaming.

Perhaps this makes me old-fashioned, but I’m a huge believer in the importance of music ownership, and the effect this has on our perception of music’s value.

So for me, the decline of download cards represents a decline in value for money. Increasingly, if I want a digital copy of a new record, my only choice is to go through the arduous task of digitizing the record myself using recording software.

Clearly, there are some costs attached to supplying cards. There’s the cost of printing, the cost of production and packing, plus the hosting cost.

However, I don’t know about you, but I haven’t exactly seen a decrease in cost associated with vinyl that doesn’t include a download card.

Moreover, I can’t help but think many record labels are missing a trick. Surely a download code is a perfect opportunity to ask fans if they’d like to stay in touch?

This, in turn, would give them further opportunities to promote the artist, and push other revenue streams, such as concert tickets and merchandise. Some labels are great at this, others, not so much.

One model that I’ve heard put forward to keep digital downloads alive is an option to contact the label requesting a download.

If the contact instructions are printed as part of the overall artwork (preferably inside a gatefold, or on the insert of standard jacket), then this would negate the need for an individual download card.

This method is not without its downsides, but it could help continue to serve fans, while allowing labels to connect with the audience.

In defense of the shift to streaming over download cards, continued listening through these platforms means the artist continues to get paid—albeit a small amount per stream.

As far as I understand, the artist does not receive any additional royalties for a download claimed off the back of a vinyl record.

So are download cards on the way out?

Sadly, it looks highly likely. Digital files are now a minority interest, with the benefits and demand too low for many labels to justify (or at least that’s how they view it). I

would argue, however, that labels who go the extra mile to make their records feel like good value for money will win in the long run. If the production costs are proving difficult to justify, then a “contact the label” option could make the most sense for those wanting to serve the remaining demand for downloads.

Despite the apparent benefits, there are still plenty of music fans who claim they will never switch to streaming. So far, I’ve been one of those people. Will this change as time goes on? Only time will tell.

Artists or labels can put any formats available for download.

Take bandcamp for example; they make you choose mp3, wav or flac depending on the artist or labels.

They can send you a code directly throught your email if you buy from a website.

With physical vinyl stores, that’s not really an option I guest.

There is no way you can’t make the file equal quality or even better than a stream if you really want to 😉

I may’ve used digital download codes a few times, but usually ignore the download card because of streaming. I think I can speak for most people who don’t download–it’s because we don’t have the space on our devices! Streaming is just so much more convenient in that regard. I still keep the download cards because I still want to own my music in case the streaming platforms take it down.

I have personally never used the download card either when buying a Record or a video where this was also the norm. The MP3 format is just not acceptable to me for digital downloads as it has such a poor quality. With streaming services like Tidal offering above CD level quality why would I listen to poor quality recordings? Interesting to see that Amazon have just moved to CD quality streaming. The MP3 version of songs may be fine for listening on phones and the like but not for serious HI FI listening.

Hi Ross There are better mp3 recordings than others. Some are dreadful as you say. But note that WAV files can be recorded on cd. So dont assume cd is always mp3 ‘quality’ although mostly they are. uality is often down to original recording techniques, not the final format. I’d go further and say the biggest con trick consumers are exposed to and absorb because most music buyers are ignorant of this, is that some/most vinyl recordings are being taken from digital masters, often because the original recordings were digital and not analogue, i.e. Just to jump on the vinyl bandwagon. I wanted to be a recording artist and still record in my own time using my money. Realistically I left the industry when I was about 22 when I realised how corrupt it was. If interested ‘Flying Umbrellas _ Percival’ is one of my albums out there on the ether. Available in WAV.